The Monologue

In today's weekly, it's time to introduce the idea of divergence as a defining theme for the U.S. economy. The most important point of divergence at present is shaping up to be the opposing direction of travel of the real and financial cycles.

While we do not believe a recession is imminent, we're not particularly excited about the real economy either. A confluence of very powerful cross-currents are essentially offsetting each other to keep activity growth positive but tepid – AI-driven investment and strong consumer spending on one hand, tariffs, a weak manufacturing sector outside AI, and a slowing services economy on the other.

Meanwhile, financial conditions are relatively easy, and getting easier. Spreads on everything except the very highest risk leveraged loans are compressing, M&A and buyout activity is picking up, and the Fed is easing even as inflation risk rises. Our Financial Factor is a full standard deviation easier than the historical average. Usually this is consistent with a fast-growing economy.

When taken together, these two trends, if sustained, point to the emergence of a re-leveraging cycle after a long period of private sector deleveraging. If the Trump administration can stay out of its own way, this has the potential to raise growth, but it will likely come at the cost of sustained above-target inflation. Either way, a pickup in deal flow will help the private markets sector to move through the challenges that have defined the last two years.

The major "known unknown" is the frothy equity market, and what would happen in the event of a serious correction given the importance of the wealth effect in sustaining consumption growth and the link between public valuations and AI investment spending.

That might be a scary scenario, but, it's not 2007. The economy is not over-leveraged, and we don't think a major correction would be a financial crisis event. It would likely look more like the early 90s, triggering a mild recession in a still-inflationary economy and re-setting an over-extended valuation environment.

The counter-intuitive conclusion is that, in part because the Fed has a bias toward activity and the labor market over inflation at the minute, interest rates would come down. This would further improve the positive environment for private equity. Fund managers would no doubt appreciate a more rational public benchmark when pitching to LPs. Lower valuations would unlock acquisition capital, though fund vintages that deployed primarily during the peak private valuation years (2019-2022) will face a tricky exit environment. Our research has shown that buyout is at its most effective during slowdowns, when opportunities to improve assets and create value are greatest.

I must end this week's monologue with the obligatory U.S. government shutdown chat, though I'm loath to crowd the field here. Frankly, for long-term investors, the shutdown does not really matter – even public markets have shrugged it off (see this week's Market Monitor below).

When will it matter? The impact on growth is non-linear, with the 35-day 2018 shutdown teaching us that after about a month, disgruntled, unpaid public employees can start to cause disruptions (flight attendants were in the vanguard last time). It's precisely when this risk materializes that politicians feel maximum pressure to resolve the issue, and a deal gets done. Public servants get their back-pay and backlogs are cleared, and the net effect is small potatoes (though we could see a hot November inflation number from pent-up demand).

Our advice is to stick to the fundamentals, and try to take advantage of the emerging sweet spot for deal making.

Weekly Macro/Market Monitor

Market Monitor

U.S. markets shrugged off the first week of the government shutdown with a distinct air of nonchalance. The S&P 500 (+1.7%), Nasdaq Composite and Dow Jones Industrial Average (both up +1.8%) all had good weeks, but what was notable was the outperformance of the Russell 2000 small-cap index (+2.7%). On balance, the week's macro news was taken as positive for smaller companies, something private markets will cheer (more on that below).

Led by the U.S., the global fixed income market consolidated somewhat too (10-year T-Note 0.2bp lower at 4.13%). Bond markets are not (yet) worried about the shutdown (further) derailing the U.S. fiscal trajectory, nor that it might knock the Fed's easing agenda off-course, with implied odds of a cut at the end of October standing at 95%. In fact, we've reached the point where not cutting would be a major statement from the Fed, and in our view the market is a bit too confident. Delayed data publication could just as easily give the FOMC a reason to pause as to proceed with interest rate adjustments.

In any case, taking their cue from the sovereign, spreads in corporate bonds and leveraged loans tightened, signaling a broad easing in financial conditions this week.

The only place the shutdown showed up this week was in a slightly weaker U.S. dollar (down -0.8% on the week), and in another +4.2% leg up in the surging gold price, which is now at US$ 8,886 per ounce, and has returned 49% year-to-date (we're at the point where any news feels like an excuse for more buying in this gold bull market).

The tone in the private equity data is good too. More September deal data will be trickling in over the next few weeks, but we can already say that it was a very good Q3 for deal flow, particularly on the volume side, as a larger average deal size pushed capital deployment well above Q2 levels, and also beat out Q3 of 2024. M&A and buyout exit activity are running at or above the 2024 pace, and the outlook for Q4 suggests that this momentum can sustain.

Macro Monitor

The key U.S. data and events this past week:

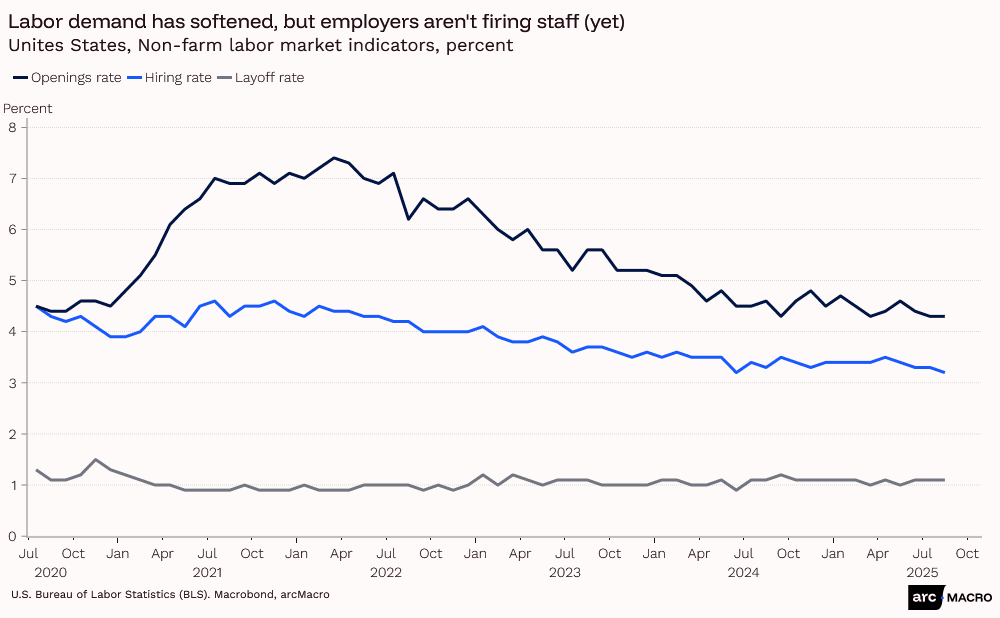

- JOLTS (Aug): Largely as expected, job openings remained weak and employers are not in a mood either to hire or fire.

- ISM PMIs (Sep): Manufacturing remained in "stagnation" territory, while Services posted a surprisingly large decline to the 50.0 mark that separates expansion and contraction.

Monitoring macro through the shutdown

Last week was supposed to be about nonfarm payrolls (NFP), which had the potential to shift expectations around the Fed's decisions in it's October 29th FOMC meeting. Alas, the shutdown denied us the now standard game of over-reacting to the NFP release, then later to the substantial revisions in the next two reports.

The longer the shutdown lasts, the more official data will be delayed. This is causing much hand-wringing for investors focused on faster moving markets, but we're not too concerned at arcMacro.

For one thing, it's easy to over-react to a few weeks of delayed data. The economy does not swithc regimes overnight, and it's unlikely we are missing clear evidence of a significant change that would alter long-term investing decisions. In any case, official data tends to be the most lagged, and most heavily revised (making it very reliable for historical analysis, but not real-time turning-point assessments).

For another, our Factor and Regime framework is designed to handle these types of issues in stride. Among the hundreds of input series we estaimte our factors on are a large number of privately-produced indices, which will not be delayed. The statistical machinery behind the Factors is able to infer what these imply for the overall economic picture, including implicit estimation of the official data.

As the shutdown wears on, we'll surface some interesting private data sources, and continue to rely on our framework to separate signal and noise.

arcMacro Factor and Regime Update

What we're watching next week

- US official data delayed: We would have been keeping a beady eye on foreign trade, consumer credit and bank balance sheet releases, but these will likely be delayed even if the government does re-open this week.

- U-Mich consumer sentiment (Friday): Inflation expectations is the key series to watch.

- Canada employment (Friday): The +0.1pp increase in the unemployment rate to 7.1% would put another BoC cut at the next meeting firmly in play.

Research Briefings

1. Consumers are staving off a U.S. recession. What are they buying?

Answer: Fun stuff and tech stuff. One of those trends is likely to prove more sustainable than the other.

Last week, we noted that the 3.2% annualized Q2 GDP growth rate in the U.S. was somewhat misleading, as it primarily reflects consumption. When factoring in B2B activity, the economy is slowing to a halt.

Nevertheless, strong consumption is a fact. For investors, especially those in illiquid markets who are taking longer-term bets, it's essential to understand what drives spending in different sectors and how durable the trend is.

The heatmap below breaks down inflation-adjusted monthly personal expenditure growth. To smooth out monthly noise, we look at the annualized 3-month over 3-month growth rate.

So, what are consumers buying?

- Technology: "Information processing" goods (which include computer equipment and software), telephonic equipment (cellphones), and communications services (internet access and data) have all returned to a high-growth trend after a soft spot at the start of the year.

- Fun goods: Recreational vehicles, jewelry, clothing, footwear, and makeup. Even books!

- Fun services: Domestic travel, gambling, even theatres and museums have all seen high demand (and these data are seasonally adjusted, so it's not summer spending).

What's weak? Motor vehicles and white goods. But this is an artifact of a pre-tariff sales surge early in the year, when households brought forward their purchases in anticipation of higher prices. It will take a few more months to get a clean view on tariff impact in this sector.

Strong recreational spending is a real puzzle. Consumers still report being highly sensitive to inflation, but that isn't stopping them from visiting Disney World or adding an ATV to the collection.

In the olden days, before COVID-19, spending on discretionary goods like this would signal a strong economy. But that conclusion is less obvious now, with households perhaps more inclined to lay down some "YOLO" dollars when the horizon gets cloudy and enjoy life while they can.

There may be a clue in the slow spending growth on restaurants and streaming services. But even here, things aren't simple. Are households trimming expenses on these luxuries first, or is demand in these challenged sectors structurally weak?

Perhaps the strongest conclusion we can take from the heatmap is that it's the top end of the income distribution who are driving spending.

The tech spending theme feels more durable. I can see the hallmarks of a shift in spending towards AI and AI-enabled services here (or, more honestly, I can't think of a better explanation than AI). Fast-growing tech categories include subscriptions to AI services and a new generation of AI-optimized devices.

This will be a category to watch in the next few consumption reports—if AI spending is showing up in consumption as well as investment, we may have a stronger economy on our hands than we thought.

2. Two speeds, one engine

Scan the financial commentary these days, and you're bound to see a post about the "two-speed" (WSJ) or "K-shaped" (CNN) economy, signaling an imminent downturn.

Correct on one count.

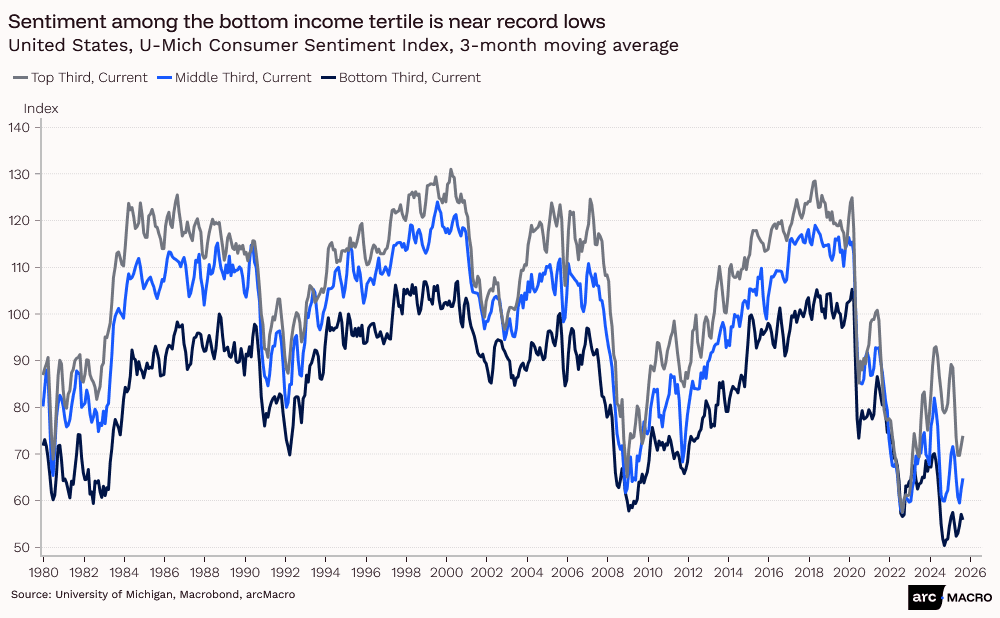

The prior briefing points out that consumer spending patterns indicate that higher-income households are propping up growth. At the same time, there is plenty of evidence from surveys and (admittedly lagging) distributional accounts that lower-income households are struggling.

But it does not follow from this that a recession is imminent or inevitable. The U.S. has been defined by this "two-speed" profile since 2022. In fact, it looks like a fundamental feature of a post-COVID-19 economy that has somehow avoided a recession, but has been unable to get annual trend growth beyond 3% (stuck in what we call a "Sluggish" regime over at arcMacro).

Looking at the latest data, I don't see any reason to believe the "two-speed" economy can't persist for some time yet.

Divergence doesn't mean downturn

Let's take a look at delinquency rates, for instance. They're going up, clearly, and in categories like credit cards and auto loans that involve the largest share of lower-income borrowers.

But we're hardly facing the kind of over-leveraged household balance sheets that turned the 2008 recession into the deepest financial crisis in a century. Banks are well capitalized. They have provisioned for losses on higher-risk borrowers and have demonstrated their ability to absorb them at these rates. This gives me some comfort that higher default rates won't spill outside the high-risk category and that the losses can be contained.

Mortgages, which typically have higher credit quality than credit cards and auto loans, and where rates have mostly been fixed at record lows for 20-30 years, have very low delinquency rates. Indeed, where there are defaults, it's because landlords are underwater on their multi-unit investments, hurt by a combination of higher interest rates and oversupply. Rental prices are soft and still deflating, according to the Apartment List nationwide index – a positive trend for lower-income consumers.

Nonetheless, the after-effects of the 2022/23 inflation surge and the pain of higher interest rates are still being felt by blue-collar workers. The Fed doesn't talk about this a lot, but the pain for lower-income households will accumulate the longer the FOMC maintains a "moderately tight" interest rate stance. The cost of squeezing out that last percentage point, getting inflation down from the current run rate of ~3% to the 2% target is asymmetrical and rising.

The problem for the Fed is that inflation is not flat; it's trending up, so the room for relief will prove limited.

It's no wonder consumer sentiment at the bottom end of the income distribution is so poor.

And if they're unlucky enough to lose their jobs, lower-income workers face a labor market that's less friendly to the unemployed than it was a year or two ago. Vacancies have dried up, and firms have stopped hiring.

Again, however, "worse" is a relative concept. On most measures (including broad unemployment, at 4.3%), the labor market looks very similar to the five years prior to the pandemic, when the conversation centered on its historic tightness.

It's the stock market, stupid

… and the stock market is AI.

The "two-speed" economy is real, but it's a distraction from the real driving force of the economy. As long as AI and related themes drive investment and fuel a stock-driven "wealth effect" that keeps wealthier Americans spending, this (imperfect) status quo will hold.

AI has probably pushed some public stock valuations into "overvalued" territory, and a correction will eventually occur. That would likely cause a mild recession.

For now, we're still in the early phase of the AI investment cycle, so my central scenario is that it will support growth for some time through a combination of investment spending, a wealth effect, and, eventually, productivity gains. That's enough to mostly offset the negative tariff impact and other economic drags, keeping the U.S. stuck at two speeds in second gear.